I looked up one day and . . . I needed an ATP rating. ASAP.

Wow. ATP. Airline Transport Pilot. The Aviation PHD. The top rung. As soon as possible. Wow.

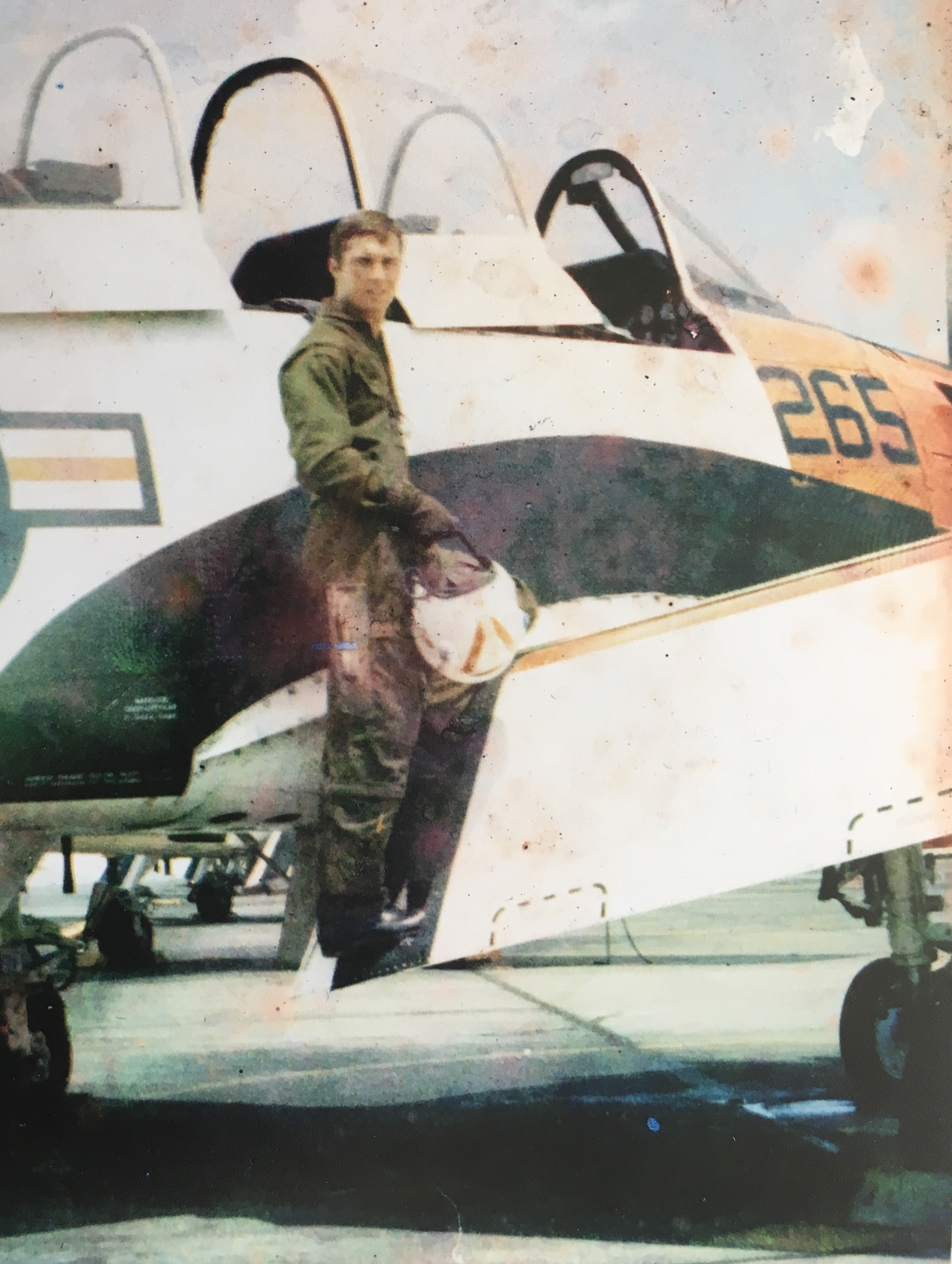

I had a start date for the simulator instructor position. The only thing I needed was the ATP rating. I easily had the flight experience requirements per PIC, IFR, multi-engine rating, cross country time, night time, etc. In the Marines I had flown a lot including most days and often twice a week at night. Three-hour flights. Hawaii and Japan, Okinawa, Taiwan. Eastern US. Lots of actual IFR. I had all of the available ratings including a Special Instrument Card, and functioned as check pilot on NATOPS standardization and instrument check rides. Back then.

But back then the instruments had needles and dials for the TACAN, VOR, ILS, and NDB. The non-precision approach was the worst with punching the clock and the MDA and no auto-throttles. Back then I had all that down pat. But now years of civilian flying had been flown in a free-spirited spartan, highly spirited cross-continent fiberglass steed with absolutely minimal “distractions” on the panel. So the new glass panels were . . . new. Quite a situation.

So I jumped in. The ATP drill consisted of two or three intense training flights and a check ride. Bang bang bang. The plane was a light twin-engine Piper Seneca trainer. Each training flight was identical to the check ride. Identical. Every element of the flight was critical. Especially exciting was the hooded zero-altitude-tolerance missed-approach turn at Dallas Exec tip-toeing up under or possibly into DFW airspace, where you simultaneously level off and switch frequencies without knowing which air space frequency or altitude they would assign until you’re there and they do it. A quarter-inch infraction with the altimeter needle triggered an actual flight violation. The tiny radio buttons required a toothpick to activate. To catch up and acclimate a little, I rode backseat on a few training flights. I observed three things about the current fighter pilots taking the course. They had little rudder awareness, they were imprinted for 140 mph no-flare smackdown landings, and they were fighter pilots.

Not being familiar with the aircraft or new radios, on my training flights I used every opportunity to learn, sometimes trying to grab something extra at the end of a maneuver. I kept looking to do an impromptu wingover, but no way. My instructor expected and demanded precise adherence to the required sequence, and rightly so. We miscommunicated on that and he mistook my couple of excursions as a negative. In the rush of time we didn’t connect on that mutual misunderstanding until I explained later over coffee, after the check ride.

The day for the check ride came too quickly. I got there early. I had seen the check pilot only from a distance. He was physically intimidating, tall, broad, shaven head, no eye contact, definitely no interaction or chit-chat.

Walking in on the big day, unfortunately, I saw one of the students in the back corner of a classroom. He worked after-hours for the flight school. He was a good kid. I admired his positioning himself to work in the school, and expected that it was a significant advantage for him. I stuck my head in and said Hi. He was weeping a little. He had failed a check ride and was out of options and time and money.

With that bright encouragement, I entered the oral exam room. White walls. White table. Seems like there was a bright light pointed in your face. The door opened. The examiner strode in and closed the door. He was wearing white. He sat down and pulled my books over and paged through them. He asked a couple of stock questions and had me explain critical engine failure. He did some scribbling. He closed the books and sat back squarely. I was thinking, here it comes.

He said, “You have one of those experimental canard airplanes, right?”

I said “. . . Yes.”

He said, “Do you remember a boy named Bryan, worked at Sherwin Williams, you gave him a ride in that plane?”

I said, “. . . Yes.”

He said, “That flight in your plane changed his life. He’s flying F-16s now. He’s my step-son and I love him as my own.”

I said, “. . . Wow.”

He leaned in and said, “. . . What would it take for me to get a ride in that airplane?”

The check ride was thorough and precise. It went perfectly, like clockwork. He complimented my airwork. You’ve had a day like that, on your game, where you couldn’t miss.

Back on the ground, the instructor was nervously waiting for me back in the lounge. He was pacing briskly back and forth like Graucho Marx with his head down and hands clasped behind his back. When I opened the door we were both a little startled. He jumped back and threw his arms up and said, “OH NO!”

At the same time I said, “All done, I passed. It went great.”

He said, “. . . OK, now, look, don’t worry, we kept a scheduling window open for you, we can get you right back up on a remedial flight and . . . What? You did what?”

I said, “All done. It went great. Perfect even.”

The check pilot walked through and gave us a thumbs up, a head nod, and maybe a wink.

My instructor stood there wide-eyed.

He said “. . . Epic.”

He threw his hands up and walked into his office.

Bill James

Fort Worth VariEze

ATP, SFTE Member, Flat Armadillo Society